‘In the Blessed Sacrament He gives us Himself again, and not only Himself as the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, no, He tells us that all three Persons will take up their residence in our hearts, if we are united with Him.’

‘In the Blessed Sacrament He gives us Himself again, and not only Himself as the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, no, He tells us that all three Persons will take up their residence in our hearts, if we are united with Him.’

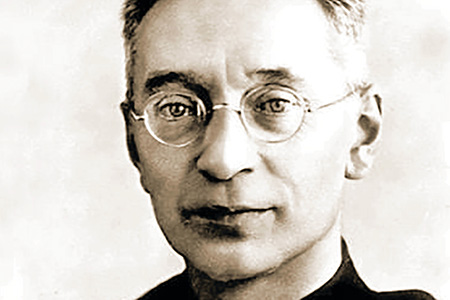

Titus Brandsma

The Eucharistic Life of Carmel

Being of central importance to the Christian life, it is no surprise to find the Eucharist at the heart of Carmelite life from its earliest beginnings. The first Carmelites built an oratory in the midst of their cells on Mount Carmel to facilitate common prayer and common celebration of the Eucharist. This sacred space was to be a focal point for encounter with one another and with the risen Lord. Until the reforms of Pope Pius X in the early twentieth century, daily receiving of Holy Communion was unusual. However, taking inspiration from the Rule of Carmel, daily reception of the Sacrament was already common in Carmelite communities long before this and was to be a constant of the life and spirituality of Titus Brandsma who entered the Carmelite Order in 1898 at Boxmeer, in the Netherlands, a town long associated with Eucharistic devotion.

Food for the Journey

Titus was convinced that our spiritual life, just as our physical life, requires food. He saw in Elijah, Prophet of Carmel, the pattern of the Carmelite life. Just as Elijah was sustained for his journey through the desert to Mount Horeb by miraculous food from heaven, so we too are strengthened by the gift of the Eucharist as we ‘walk in life’s journey here below.’ Imprisoned on account of his fearless defence of the freedom of the Catholic press and basic human rights in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands, ‘walking in the strength of the divine bread’ was ultimately tested for Titus between January and July 1942 as he followed his own ‘way of the cross’ all the way to Dachau concentration camp.

Frequent Communion

Titus’ conviction concerning the importance of frequent celebration of the Eucharist was confirmed in reading Carmelite saints such as Mary Magdalene de’Pazzi and Teresa of Avila. Titus also draws out the importance of daily reception of Holy Communion when presenting the life and message of Saint Lidwina of Schiedam, one of the national saints of the Netherlands.

Prayer after Communion

In continuity with another key aspect of the Carmelite tradition, Titus emphasised the importance of taking time to pray after receiving Holy Communion. This is a true contemplative moment when, having received the risen Lord into ourselves, we seek to open ourselves to his accomplishing great things in us. Titus reflectively links prayer after Communion to the figure of Elijah: ‘In the caves of Horeb God spoke to the Prophet by the voice of the gentle, whispering wind.

The Lord was not in the storm nor in the earthquake, but in the gentle wind. So, after Communion we must contemplate under the Eucharistic species and in the depths of our spirit; for now God passes.’

Spiritual Communion

St Teresa of Avila often recommends acts of spiritual communion when reception of the sacrament is not possible. Perhaps early on Titus might not have realised how important this would prove to be in his own life, just as readers of St Teresa in our own time might not have realised how important spiritual communion would become in time of pandemic.

While Titus was able to receive Holy Communion at Dachau (including on the day of his death), there were times this was not possible. Unable to celebrate Mass at Scheveningen prison Titus describes how ‘each morning I kneel down and say the prayers of daily Mass, spiritual communion.’ In the camp at Amersfoort Titus led communal acts of spiritual communion with his fellow prisoners.

The Eucharist and Contemplation

An often-repeated spiritual teaching of Titus Brandsma is that ‘the mystical contemplative life is a fruit of the Eucharistic life.’ The Eucharist is what strengthens us to receive the gift of contemplation from God. And such contemplation leads to action.

Titus told a group of young people: ‘Good deeds no longer suffice; they must originate in the consciousness that our union with God obliges us to perform them.’